Rv-15 Aircraft - But it wasn't until the plane showed up here at KOSH that we got our first good look at it. Here are some of the observations we made about this plane, which, it is clear, is so much more than just the first high-wing model from the world's most successful kit plane maker

Seat adjustment is done by raising a lever on the right front of the seat, then sliding the seat forward or aft while holding on to some structure on the door post. Designers are still trying to decide where to put handholds in the cockpit, since they designed a structure that does not require steel tubes above the glare shield and behind the windshield, as are typical with high-wing airplanes.

Rv-15 Aircraft

Strategically placed handholds will be an excellent alternative, and a good trade for the clear visibility of the unobstructed window. There is currently no boarding step, something that most average-height humans will want to help get in and out of the -15.

What’s A Test Article?

But such amenities aren't required for a test airplane, and the design team has some ideas about how to add them without compromising on drag. Overall, the control system is conventional in that cables connect from the pedals to the rudder and the control sticks activate the stabilator through a pushrod—these are concepts Van's is well familiar with.

For other Van's models, roll control is also via pushrod, and one might wonder how that works with a high wing. (With a low wing, pushrod-activated ailerons are almost trivial from a design standpoint.) All day long, crowds of curious people carefully walked around the RV-15, commenting on its sheer size, beefy landing gear, and fat tires.

The size of the fuselage interior and the baggage door—the latter is drawn on the prototype—gained a lot of attention from people who like to have lots of room for their gear. The existence of the first Van's high-wing plane was no secret.

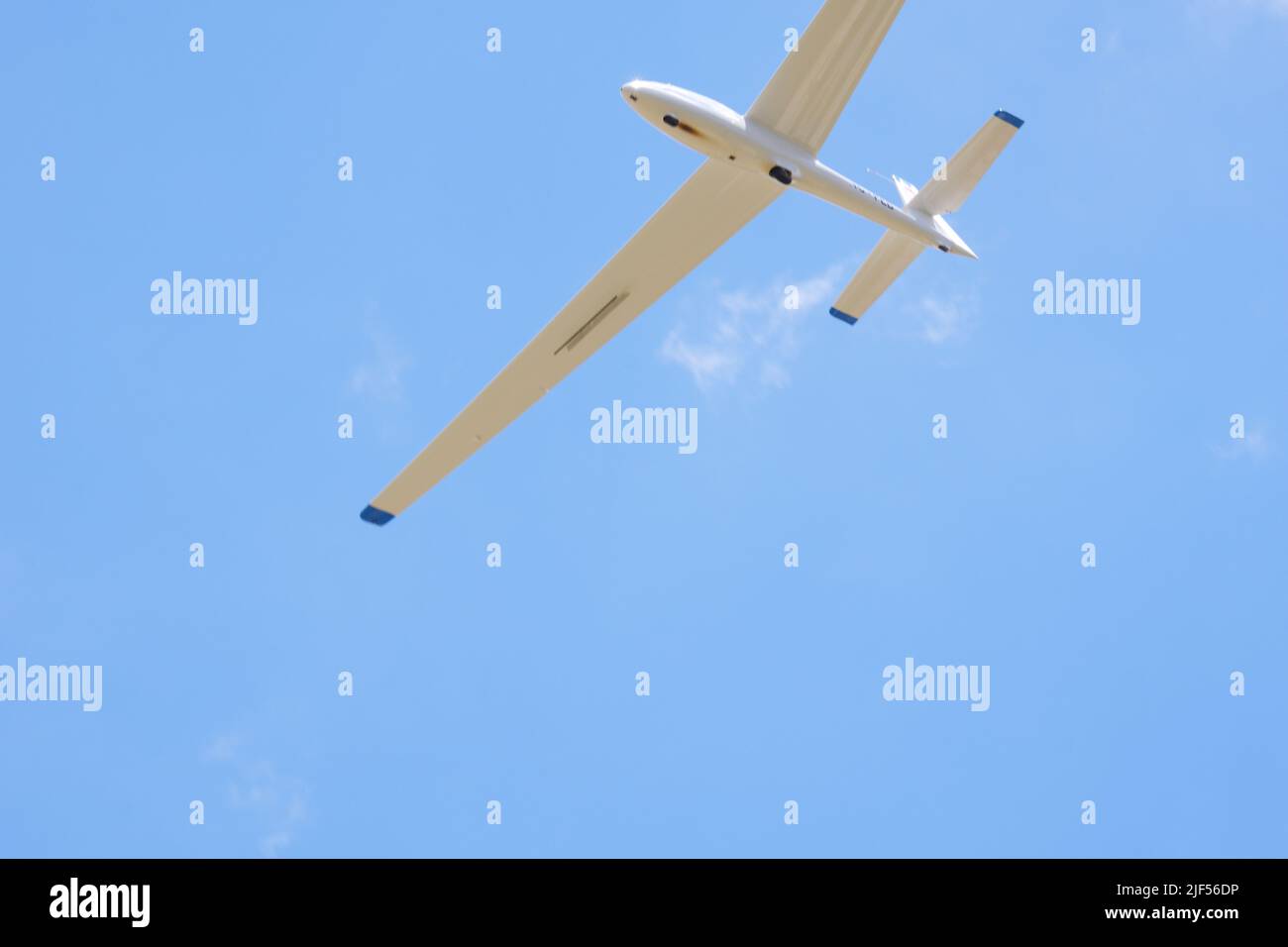

Rumors had been floating around for years that the Oregon kit giant was considering a high-wing model, in part, people assumed, to capitalize on the great interest in backcountry flying. Then, a couple of weeks ago, spy video emerged of a high-wing plane flying around Van's home airport, Aurora State in Oregon, and, well, pretty much everybody assumed, correctly, as it turned out, that the plane in question was

The Cockpit

the much-rumored new high-winger from Van's. With the cat effectively out of the bag, Van's came clean in advance of the Oshkosh AirVenture fly-in and revealed the existence of the RV-15, although not much more than that.

Built using CAD-designed parts and match-hole technology, the prototype was put together with parts produced from punch presses and CNC machines directly from design drawings. This was not cut and pasted by hand, as past prototypes have been—theoretically, production parts for kits can be produced from the same files that made the test article.

But a lot of testing will go into the machine before the first customer receives any kit parts and Van's is happy with the design. Van's salespeople noted that orders for the new design are not being taken yet, because the test flying hasn't been completed, so they don't have all the data needed to determine if any tweaks or changes need to be made before the kit enters

production. The design is meant to accommodate four-cylinder Lycoming engines from 180HP to 220HP. The engineering test prototype has a four-cylinder Lycoming IO-390 EXP-119 engine that outputs around 220HP and drives an 80-inch composite Hartzell Trailblazer propeller.

The Metal We Have

While we have not yet determined the actual speeds or useful load for the final design, we have established design targets of 140kts and at least 900 pounds, with the room to load two full-size mountain bikes in the baggage area without having to completely disassemble

them (just remove the front wheel like you would when mounting to a car or truck bike rack). Bottom line, then: What will be kitted may be much like the test vehicle, it might have some minor changes that don't really change its performance or mission profiles or it might have such significant differences that this view of the RV-15 is

akin to seeing a child's drawing of one as opposed to sneaking a peek at the CAD drawings. It's been reinforced in our meetings with Van's that many aspects of the design remain to be proven.

Assume things will change. How long will it take? They won't know until flight testing is much further along. Van's Aircraft at 50 is a remarkable company with an incredible history and a full product line—of low-wing aircraft.

Landing Gear

Whether you want a single-seater that is a nimble high performer or you want to carry four adults at 170 knots for 800 miles, you can find the airplane of your dreams from Van's—as long as it is a low-wing machine.

Basic math says that Van's has come out with a new model every 3.57 years (50 years, 14 models if you count tricycle-gear variations separately), and it has been a few since something entirely new has come out of Aurora.

In these days of computer design and computer-controlled production machinery, a smart company will try to design both their test articles and prototypes to the standard that they hope to achieve in production versions. That way, if the test article is a home run, with few changes required, they can roll into production very quickly.

The important distinction is that you use a test article to learn things that you need to know before building a prototype. The developmental prototype is then what you use to figure out what the product that you want to sell will look (and fly) like.

Where To From Here?

Prototypes are still subject to change at all levels—aerodynamically, structurally or in systems. Changes can be minor (where and how to place the baggage door) or major (a new tail). Speculation was heavy as AirVenture approached last year—after a hiatus of two years—so it was with great celebration that Van's announced that, yes indeed, there would be an RV-15!

And there was significant discussion when they added "...and it will be a high-wing, backcountry-capable aircraft with sticks." And that was all the details they would offer at AirVenture and, amazingly, little more has leaked out since then.

Sure, there were online memes and forum speculation, including a few snapshots of Maules and things with "RV-15" badly Photoshopped on the tail, but the actual airplane kept a very low profile through much of 2022.

An airplane that will get you there reasonably quickly, get down and stopped and then back off the ground in short distances, while letting you carry all the stuff you need to answer the question, "Okay so we're here, what are we gonna

What We Know So Far

back?” Fish, bike, camp, hunt, whatever you can think of. You choose. The shock absorbers will provide both spring and damper functions so that landing loads are absorbed without the plane being rebounded back into the air.

The tailwheel is similarly sprung, with a vertically oriented shock absorber connected to a custom-CNC-machined pivot block that is mounted to an arm hinged to a point on the fuselage about 10 inches in front of the shock.

The result is a long-travel gear that should be able to take quite a pounding, plus the linkage allows the tailwheel pivot to have constant camber even with a significant amount of travel. Main gear is currently sporting 6.00×6 tires on Berringer wheels (and brakes).

Current plans are to fly it on those, but they have a set of 26-inch bush wheels sitting in the shop for use on the plane—that is their default size for "bush wheels." They have incorporated provisions for an easily installable jack point on the gear, inside of the axle, to make jacking easier.

The Basic Airframe

We tend to use the term "prototype" a bit loosely. Some are really better described as test articles, which are really "proofs of concept," something that a designer (or a company) does to learn more about what they really want to design.

A good aviation example from the last century would be the X-plane series of aircraft built by industry to specifications provided by NACA, NASA, the Air Force, etc. From the X-1 through the X-15 (and continuing on to today's X-40-something), these aircraft were not designed to be prototypes of anything: They were specific aircraft designed to study things like how to go supersonic or hypersonic,

how to fly into the edge of space or how to control an unstable aircraft using computers. And before we leave the cockpit, let's answer the obvious question I know is out there—can you add a back seat?

We talked about it with the design team, and they are well aware that someone is going to add one or two. The current design doesn't preclude it, but it also isn't specifically designed with anchor points or extra structure.

Push Or Pull?

Nevertheless, the current thinking is that the RV-15 is a two-seat airplane with a generous baggage capacity. The RV-15 will prove its place in the sky—and in the marketplace—within time, and we look forward to seeing them in numbers all over the backcountry.

We're not sure when that will be, but we are certain that Van's success over half a century will continue, and another "total performance" machine will swell the ranks of E/A-B aircraft everywhere. The roomy cockpit is designed with two seats, which are mounted on rails for easy adjustment as well as easy ingress and egress.

The seats in the test article are actually from another (unnamed) airplane and are being used to "get it flying." Cockpit controls feature a standard control stick that has been shaped with a large curve to avoid contacting the seat or the pilot's legs.

In fact, we were shown a couple of different sticks that will be tried, to see which the test pilots prefer. Rudder pedals likewise featured two different designs, one for the pilot, one for the copilot.

Firewall Forward

Test pilots will use both and decide which gets the nod for incorporation into the kit. The pedals feature toe brakes, as is typical on Van's aircraft. Engine controls are conventional push-pull knobs mounted under the center of the instrument panel.

We can tell you that the engineering behind the RV-15 is extensive and first-rate, and benefits from a top-notch team. Besides longtime Van's engineer (and current president) Rian Johnson, there's Rob Heap, formerly with Scaled Composites and Cessna.

Brian Hickman recently engineered for Glasair Aviation. Another recent addition is Axel Alvarez, a graduate of the U.S. Navy Test Pilot School (as a civilian) and highly experienced test pilot and engineer. These professionals join many Van's stalwarts to help make up an impressive 12-person engineering and prototype-shop team—and Van himself is only a phone call away for a carefully expressed opinion.

The luggage area is built large—large enough for a couple of small bicycles, a full set of camping gear, a couple of dogs—or maybe an elk, if hunting is your thing. There was no baggage door when we visited the factory in June, but the frame for a large baggage door was sitting on a worktable, ready to be installed when they have the time.

Number Numbers Who’s Got The Numbers?

How large? Big enough for a cooler—or for a medium-sized person to crawl through without extensive cave exploring training! And the design goal is to have the bottom edge of the door flush with the luggage area floor, so that you don't have to lift items in and out—they can slide through the door easily.

Counteracting all this wing is a horizontal tail consisting of a stabilator. The current stabilizer has a removable leading edge for easy replacement should it become dinged up in the backcountry—or if Van's decides they want to try something else.

A stabilator was chosen instead of a conventional horizontal stabilizer and elevator to provide a wide range of pitch control for the large flaps. An added bonus is that the stabilizer will hopefully prove to be lighter, as it gives more power for less area, which means less weight.

The test article's stabilator uses two different tabs—one is the trim tab and the other is an anti-servo tab. Stabilators in other designs—think Piper Cherokee—move the anti-servo tab for pitch trim. Now, back to the RV-15 itself.

It is indeed a high-wing, two-seat backcountry airplane with a large cargo allowance that can be lifted by its IO-390 engine. It is a hefty airplane—not six-seat hefty, but easily the size and weight of a Cessna 170, which is large by homebuilt standards.

Compared to other two-seat high-wings on the market, it is different—so how did Van's come to this configuration? Well they didn't just pull it out of the employee suggestion box. Van's has been asking their customers for several years now what they would like in the next model, and they have been listening—as hard as that can be when you ask a large group of pilots what they want.

The noise in the virtual room has been tremendous, with lots of great ideas tossed about. What about fuel? The first article has 40-plus gallons of fuel in a handmade tank fitted where a passenger would go.

This is for several reasons. First is to ensure that the first flights would have a conservative CG loading. Second is that Van's hasn't decided if the fuel, to be carried inboard in the wings, will be in separate tanks fitted into the wings, or if the wings will be "wet" like most RVs are.

(Remember the aileron pushrods go through the wing D section, so, if this is the configuration used in the kits, fuel can't go there.) Final fuel capacity is also still being discussed—but the engineering team wants to provide maximum flexibility

in loading and range for the pilot, so our expectation is for bigger rather than smaller. Let's call it in the ballpark of 50 gallons. The fuselage is all aluminum and has forward and rear wing spar carry-through structure as part of the cabin ceiling.

There are large entry doors on each side of the cabin, with steel-tube-framed plexiglass doors covering the openings. The doors are hinged on their front edge but have quick-release pins on the two hinges so they can be removed in about 10 seconds to allow open-door flying.

Although the doors may look bulged out, they actually follow the contour of the fuselage. The cabin feels and looks roomy. The engineering team is not certain that the doors will be rugged enough as-is, so they might be iterating on the design with a beefier armrest or other structure.

Let's talk about the gear. Both the main gear and tailwheel are using TK 1 Shock Monster shocks for their action—a proven brand out of Lincoln, California, that is equipping a large number of bush aircraft.

The main gear is unlike anything Van's has designed before, with two separate aluminum legs hinged at the lower corners of the fuselage. Part of the leg extends upward, above the hinge point, and is connected to the large shock absorbers that are oriented across the fuselage laterally and are sandwiched between the belly skin and the floorboards.

For now, the maximum gross weight is 2050 pounds. Again, this is the test article. Van's hasn't said if that's the final weight goal or not, but our guess is that it isn't. There's a lot of wing on this airplane—easily 170 square feet or more—which would support higher gross weights while maintaining a low stall speed for good backcountry airfield performance.

Then again, it's not out of the realm of possibility that this is more wing than Van's finds optimal. So much could change. Let's wrap up by talking about expectations. The RV-15 likely to be unveiled at AirVenture is a huge achievement for Van's Aircraft—it represents years of market surveys, design and manufacturing work using everything they have learned over 50 years of innovation and production.

As we write this, no one has flown it except the Van's test team—although we hope to get a crack at it soon. And realistically speaking, we expect that there are going to be design changes to make "it works" go to "we really like it!"

With such a radical departure from previous Van's designs, we have to expect that control harmony will be improved and tweaked until Van is happy to put his name on it. Visibility from the cockpit on the ground appears to be excellent.

Comparing it to similar taildragging high-wings, I'd have to say that it is superior to most. The upright seating allows you to easily move your head forward to see around the forward door post if required to see what's coming up in a turn.

And the view over the top cowl was excellent for taxiing. The design eye height is fairly high in the cockpit, and an extra cushion (on top of the temporary seats) was required to get my average height up to that level—but once I did, it sort of felt like I was sitting in an

Air Tractor, casually surveying a large domain. I liked it! The RV-15 is still not at the prototype stage, and although it was built from CAD models that can be replicated by the push of a button, we expect that significant tweaking could happen before any kits are shipped.

It is possible that the tail might change, or that the ailerons might need more or less area. If the ailerons have to change, that means the wing changes—and no one is going to want to "un-build" their kit to change things drastically.

Manuals have to be prepared, and the factory tooled up to produce the new kit. So when will the kits be available? We expect it will be a while—but the wait will be worth it. Rian Johnson, president and chief technology officer, understands that you have to pull all of the information together and look for consensus—you can't give everyone what they want because many ideas are diametrically opposed.

When we have looked at the market ourselves, looking for a niche that hasn't been filled, we have come to the conclusion that Van's has hit an open spot with the RV-15—it's larger than LSA-capable machines, smaller than a

Moose—and right where the burgeoning backcountry market is looking to expand. It's a load hauler that can get you from the flats to the mountains in reasonable time, with enough camping gear to keep you there in style.

The market spoke, Van's listened, and they gave the most they could to the largest number of potential builders. The trike is likely to use an RV-10/14-style nose gear and a more common aluminum leaf gear with a less complex fuselage structure;

the thinking is that the trike is less likely to be taken far into the backcountry and therefore does not need the weight or complexity. I was told flat out that they would not try going head to head with the NX Cub.

Here's where you might end up confused. The test airplane you see here—and might have crawled through at AirVenture—does not represent the likely final form. This airplane carries a series of pushrods and bellcranks to translate stick motion up through the aft door frame (the B pillar), with a short torque tube and then a long pushrod that's actually just ahead of the aft spar.

From there, a bellcrank and short pushrod connect to the aileron. When will it be ready? I'm sure that the standard homebuilder response of "Tuesday" is probably accurate. With the first flight just a month before the AirVenture debut, it is far behind the test curve of, for example, the RV-14.

That airplane was introduced by surprise at AirVenture 2012, but it had been flying for a month before its debut. Tail kits weren't being delivered for quite a while after that, and fuselage and wing kits followed.

And while there were tweaks, the first customer airplanes were very much like what was seen at AirVenture that July.

rv15 specs, vans aircraft forum rv15, rv15, rv 8 rc plane, vans rv15 price, rv 7a